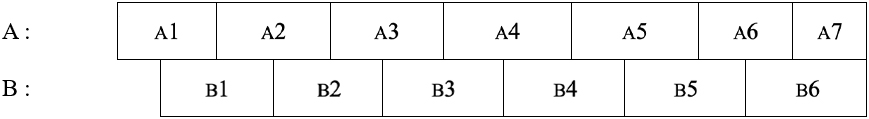

An issue of great importance—one of the most significant in twentieth-century music—was the following structural problem: how can relatively short and isolated musical ideas be combined so that their assembly creates a coherent, organic whole, with clear signs of continuity for the listener? To solve this challenging question, Lutosławski employed a brilliantly simple yet effective technique, known from earlier music traditions (such as old polyphony and the works of Brahms and Shostakovich). This technique achieves continuity by running the musical flow on at least two parallel planes (labeled a and b in the diagram below) in such a way that the boundaries of their individual segments (a1, a2, ..., b1, b2, ...) do not coincide.

As a result, potentially disruptive transition points between segments are effectively smoothed out. This approach is reminiscent of the way bricks or stone blocks are laid in wall construction, using patterns called "ties" or "wefts" in engineering. However, Lutosławski preferred to compare these constructions to chains, with their overlapping links. This is where the term “chains” as a customary name originated.

Chain shaping of form occurs in the works of Lutosławski, not only in those from the 1980s, which he explicitly called Chains. This principle can also be observed in earlier works, such as the Passacaglia from the Concerto for Orchestra(1954), the main movement of Mi-parti (1976), the cello piece Grave (1982), and the entire Partita (1984). The earliest known example of chain form appears in the Bucolics for piano (1952), while one of the most elaborate examples is the first orchestral Postlude (1963). (The latter two cases have been analyzed in detail by Marcin Trzęsiok in his excellent study Chain or Polysyntax. Problems of Formal Punctuation in the Music of Witold Lutosławski on the Example of “Bucolics” and “Postlude I”, Aspects of Music 2022, no. 12.)

The years 1947–1957 marked a breakthrough period for Lutosławski, opening entirely new musical perspectives.

In 1947," said the composer, "when I finished writing Symphony No. 1, I realized that the language used in that work would not take me [...] where I wanted to go. I believed that in order to learn some meaningful use of the traditional twelve-note scale [...] I had to start from the very beginning, for there was nothing out there that could be applied in any way to the purposes I dreamed of at the time: neither tonal music, nor post-tonal music (in which I had written a number of works), nor dodecaphonic music. Therefore, I decided to start almost from scratch. [...] I began my work by studying marginal phenomena in the field of harmony within the framework of the traditional twelve-tone scale. These extreme phenomena are consonances containing all twelve notes of the scale [...].

Witold Lutosławski, from the texts On Music Today. On His Own Works (“Preludes and Fugue”) and Meditations on the Composer's Workshop, in: O muzyce. Writings and Statements, edited by Zbigniew Skowron, Gdańsk, 2011

The phenomena in question, known as "twelve-steps," are based on the equal material of the twelve chromatic elements of the octave (pitch classes). Each twelve-note arrangement represents a different ordering of the initial twelve pitch classes within the available registers, with each pitch class appearing only once in principle. The relationships of similarity and contrast between these arrangements enable the creation of sound sequences with highly varied characteristics.

For example, in the song Church Bells, the final piece in the cycle Five Songs to Words by Kazimiera Iłłakowiczówna for voice and piano (1957), Lutosławski combines two twelve-note sonorities in strong opposition: “mild” and “sharp.” The expressive dissimilarity of the sonorities arises from differences in the interval types between their successive elements. The same set of pitch classes (c, c#, d, d#, e, f, f#, g, g#, a, a#, h) is presented in two extreme and contrasting orderings:

- Sharp arrangement: A-d-f#-c1-d#1-f1-g#1-h1-g2-a#2-c#3-e3 (interval sequence: 2-11-6-11-2-7-2-5-6-5-2)

- Gentle arrangement: C#1-D#1-D-G#-g-a-e1-f#1-h1-f2-a#2-c3 (interval sequence: 5-4-6-3-2-3-3-8-3-3-3)

The criteria for classifying and combining twelve-note structures in Lutosławski's music include the type of tetrachord forming their lowest layer, the distribution of minor ninths and major sevenths, and the presence of asymmetry or symmetry in the disposition of intervals. The twelve-note structure may appear in a composition as an actual vertical sonority, but more often it serves as the framework for layered figurations or even a single melodic line. In Lutosławski's post-1957 oeuvre, it is common to divide such structures into distinct layers differentiated by instrumentation, rhythm, and texture.

On November 11, 1964, Zygmunt Mycielski noted:

[Lutosławski] showed me his String Quartet. It is written only in voices, without a score; the voices play together and have figures to perform at will. They give a cue, and another instrument performs these figures—basically a series of intervals from which one creates, at some level (pitch), a kind of moving 'position.' Lutos told me that he only felt free, with the door open, when he broke away from that absolute verticality and began to move in a world where there is no bar line and rhythm can be notated freely.

He also has a rhythm notation machine that taps—a roller with paper that spins, on which you can put dots and dashes by holding down the graphite. This allows you to notate rhythms that can't be written down [in the traditional way].

Zygmunt Mycielski, Journal 1960–1969, Warsaw 2001

Mycielski's words describe one of the most significant structural techniques in Lutosławski's music: playing ad libitum(Latin for “at will”), also referred to as the technique of “controlled (or ‘limited’) aleatorism.” At designated points in a composition, musicians perform their parts with a degree of rhythmic freedom, lengthening or shortening the written notes without adhering to a common pulse, independent of the playing of other performers. The result is a sustained, jittery “stain”: a shimmering, dense, and static sound that, through the planned arrangement of pitch, fuses strictness with freedom, chaos with higher order.

Lutosławski's aleatorism, one might argue, transfers into the realm of ensemble performance a well-known phenomenon traditionally referred to as tempo rubato. Aside from the rhythmic indeterminacy (within narrowly defined limits), it shares no connection with the technique of improvisation: the performer does not assume the role of the composer.

Lutosławski,” wrote Konstanty Regamey, “demands that performers perform freely, not compose freely. [...]

[...] The important aspect of this method is not so much that the new structural arrangements each time do not have a strictly measurable course (though the notation gives some guidance: short or long notes, shorter or longer pauses between individual notes, the grouping of certain notes, etc.), but that these indeterminate structural courses overlap with as much independence as possible. This gives rise to highly complex, unquantifiable polyrhythmic structures that are impossible to notate, but which nevertheless have an organic and natural character, since the performers are freed from contractual, anti-musical restraints and the constant compulsion to suppress spontaneous reflexes (which they are often forced to do when performing conflicting and strictly written polyrhythmic runs).

Of course, such rhythmic-agogic independence of individual lines indirectly affects the resultant consonance, but the choice of other parameters—primarily pitch—is so precisely thought out by Lutosławski in these lines that each realization of a given section corresponds to his intentions. Therefore, the seemingly free interplay of permanently independent lines never leads to sonic clutter in his work, and, above all, is constantly protected from the greatest danger of “collective aleatorism”: falling into “gray sound,” into blandness and banality [...].

Konstanty Regamey, Notes on remarks on aleatorism, in: idem, Wybór pism estetycznych, introduction, selection, and compilation by Katarzyna Naliwajek, Kraków 2010

Since the creation of Venetian Games (1961), the ad libitum technique has appeared as an element in almost all of Lutosławski's works. Following his example, other composers, both Polish and foreign, also introduced it into their music. Lutosławski used it consistently in instances—such as climaxes or episodes of the opening movements of a two-movement form—where the dramaturgy of the composition required music to “stand still” rather than “move forward.” The harmonic basis of the ad libitum sections was usually (though not always) formed by the composer's characteristic twelve-note arrangements.

In his experiments with compositional form (“the distribution of musical content in time”), Lutosławski developed a particular solution over the years: an arrangement in which a series of short and capriciously variable episodes with deliberately dispersed dramaturgy form the introduction to a more broadly developed episode, integrated expressively and developed continuously.

The whole,” said the composer, “consists of two parts, the first of which is, in a way, of lesser importance than the second; it is a preparation, an ‘engagement,’ but does not constitute a ‘fulfillment.’” The first part consists of a series of episodes punctuated by some recurring element—in different variations. The second part—more essential and aimed at ‘accomplishment’ or ‘fulfillment’—is the basic part and no longer consists of short, miniature fragments.

Tadeusz Kaczyński, Conversations with Witold Lutosławski, Cracow 1972

The source of inspiration here was certainly the study of the works of the Viennese classics (the contrast between linking and thematic sections in the great forms of Haydn, Beethoven, and Mozart), and the closest, it seems, was the atypical dramatic plan of Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 43 (1902) by Jean Sibelius, whose output Lutosławski valued extremely highly.

The earliest examples in Lutosławski's music (and also the most typical) of such a structured form are two compositions written in the 1960s: the String Quartet (1964) and Symphony No. 2 (1967). The same scheme later appears in the composer's works many times, but rarely in its pure form. Dating from 1969, Livre pour orchestre is divided into four chapitres (“chapters”), the first three of which (taken together with the intermedia that precede them) form an introductory segment and provide an introduction to the climactic “chapter.” An even greater number of “introductory movements” are found in the Preludes and Fugue for 13 Strings (1973) and the orchestral Novelette (1979); these lack a “recurring element” (refrain). The form of Les Espaces du sommeil (1975) and Symphony No. 3 (1983) expands the basic model with a substantial introduction, epilogue, and coda. The last in Lutosławski's oeuvre, the Fourth Symphony (1992), despite its perceived bipartite nature (a distinctively marked introduction), no longer has anything in common with the scheme described here, as does the Mi-parti (1976) that serves as its model.

The term “two-part form” – which is appropriate in relation to the String Quartet and Symphony No. 2 – turns out, as you can see, to be not entirely accurate and could lead to misunderstandings. Lutosławski's idea is much more accurately characterized by the French terms introduced as movement names in the score of the latter composition. Therefore, instead of describing it as having a two-movement character, one should rather refer to the “hésitant-direct” scheme, which in Polish means “hesitant-direct.”